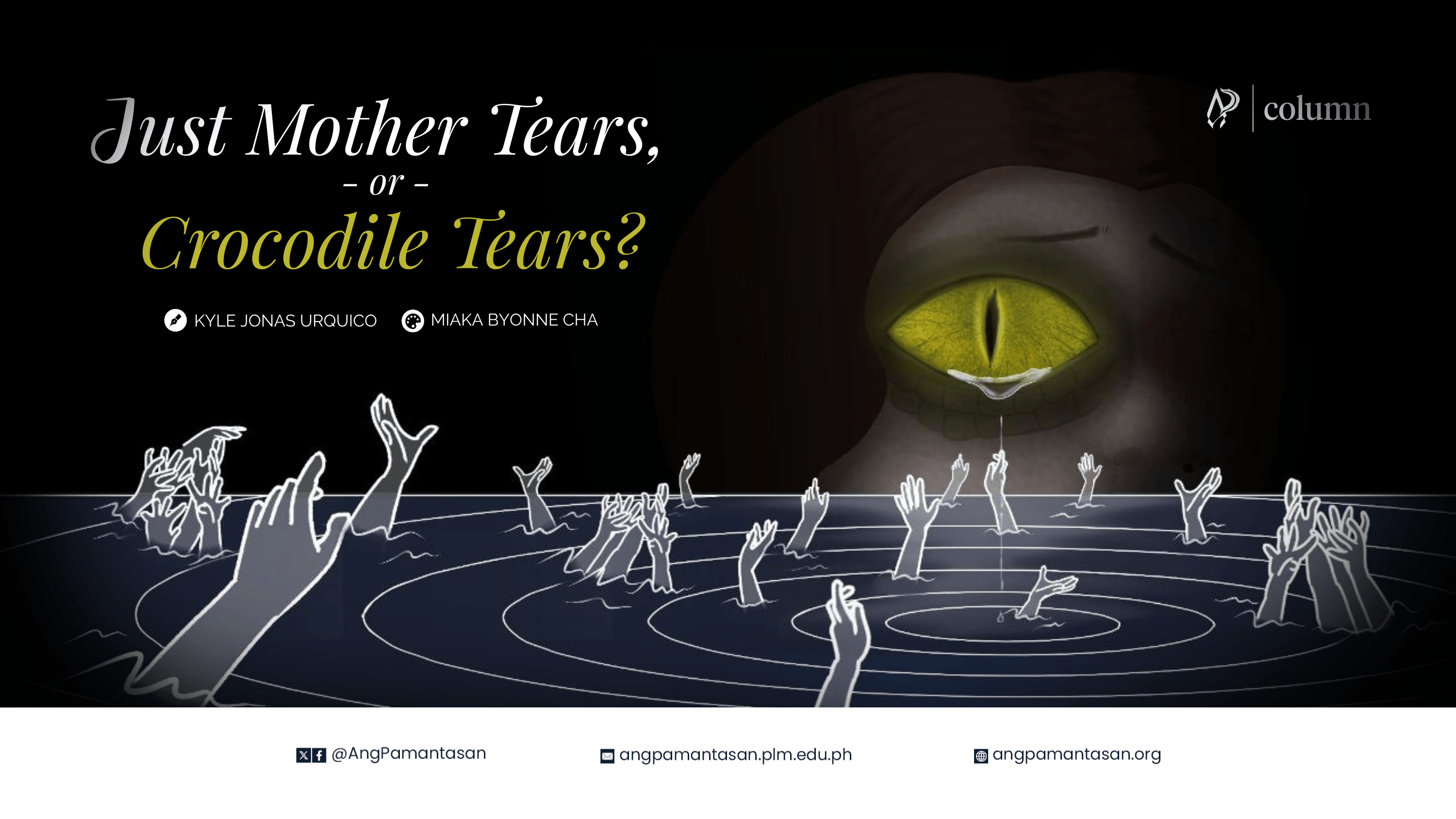

Just Mother Tears, or Crocodile Tears?

Written by Kyle Jonas Urquico • Illustration by Miaka Byonne Cha | 7 January 26

In Filipino culture, the idea of motherhood is often viewed as an instinctive sympathy and unquestioned compassion from a mother to her children. It is therefore not surprising that contractor Sarah Discaya shed tears for her children in an interview conducted in the first few days of her voluntary custody under the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI). This came before the recent issuance of an arrest warrant for allegations tying her to corruption in government flood control projects.

But sympathy is not accountability; motherhood, no matter how deeply respected, does not exist in a vacuum.

Amidst this public display of vulnerability, one flood-sized question demands to be asked: in the face of serious allegations surrounding flood control projects linked to their family’s construction companies, is it acceptable to frame the narrative around her personal and maternal suffering? At what point does the performance of suffering begin to eclipse the gravity of the accusations themselves?

During the interview, Discaya acknowledged her children’s mental health conditions, explaining that their separation was particularly difficult because all four have Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). No one disputes that such circumstances are difficult, especially for a parent. But context matters. This emotional moment came after Discaya’s voluntary surrender to the NBI: a move her family insisted was a strategic legal move, and not an admission of guilt.

And this is precisely where public patience wore thin.

While the cameras focused on this woman’s tears, millions upon millions of Filipinos continue to grieve losses that were not temporary, not symbolic, and not reversible—year after year, floods devastate communities, claiming lives and erasing entire families—disasters that repeatedly raise alarming discussions about the effectiveness, integrity, and corrupt oversight of publicly funded flood control projects.

Instead, Discaya should cry about Krizza Espra, who lost 10 members of her family in Cebu after floodwaters swallowed their house during Typhoon Tino. Or, is she aware of the tragic story of Frances Angela Garilao Pecson, whose last act before losing her life during the same disaster was to heroically save both her two-month-old child and her own mother? These were not isolated tragedies. These were not anecdotes for emotional contrast. They were part of a recurring national trauma. They were the human cost of systemic failure.

A failure that the Discayas have been accused of being heavily involved in.

Because casualties have been piling up on a scale so vast, it has begun to blur into statistics. Behind every number is a family that is permanently broken. Sarah Discaya may weep over separation from her children, but she remains alive with the prospect of reunion, with the bonus that her children are financially well-off.

Compare that to the thousands of parents and children in vulnerable communities that were denied even mere mercy, whom after the storms struck, were left with nothing.

Against this reality, public displays of grief by individuals linked to projects under investigation inevitably ring hollow. The imbalance is simply stark; the disaster victims mourn loved ones carried away by the floods, while others retain wealth, safety, and influence accumulated through years of government contracts tied to infrastructures that fail the very people they were meant to protect.

Let us be clear: this is not a debate about whether a mother is allowed to cry. It is a reckoning over responsibility. It is about whether those who benefited from public funds are willing to confront the consequences of alleged failures that left entire vulnerable communities exposed. It is about whether or not the recent developments—mounting investigations, and now an arrest warrant—might have arrived far too late for the victims. They at least have the right to ask. After all, it is their money. Contractor money is taxpayer money.

Participation in systems that allegedly produced widespread harm carries moral weight. Profiting from them carries even more. While legal judgment has begun to be rendered, the ethical reckoning had long since begun in the court of public conscience.

But still, full justice remains to be served. Until it is, public outrage should not be directed at tears shed on cameras, but at the billions of taxpayer money misused, the lives lost to preventable tragedies, and the enduring absence of meaningful accountability from those who held power, contracts, and control.